A complex story

Mining in Questa is not a simple issue. On the one hand, the mine provided significant economic opportunities for local residents. At one time it employed 750 workers and was the largest private employer in Taos County. The mine’s owners funded infrastructure in the village, such as a local park, streetlights, and the new solar array. On the other hand, the mine polluted the Red River and local watershed and posed potential health risks, both to employees through the dangers of daily mining operations, and to local residents through exposure to mine-related pollution of local water, air, and land.

Environmental and economic challenges continue. Questa’s mine produced Molybdenum, a hardening agent for steel.

Through the simple acts of owning a car, cooking with cast iron, or digging in a garden with gardening tools, one is likely reaping the benefits of molybdenum. Most lifestyles inherently create a demand for this resource.

Historic mining in Questa

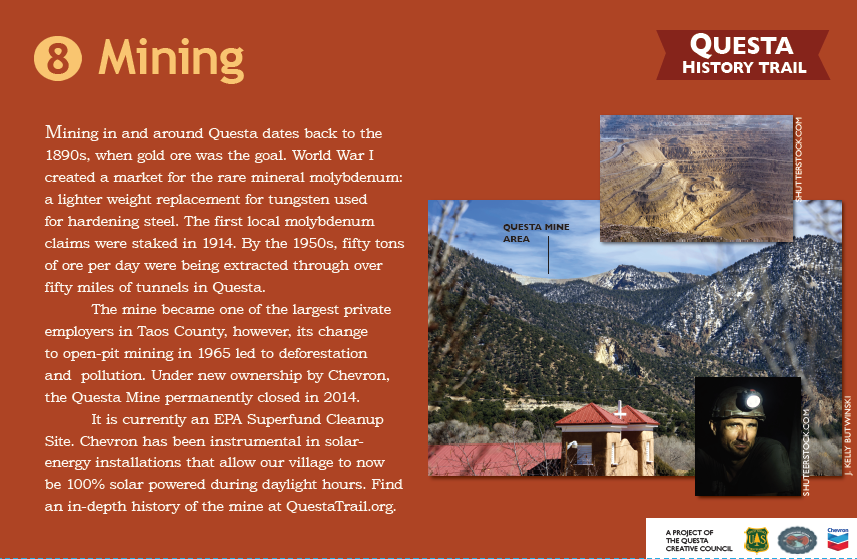

The hills of northern New Mexico saw much hard-rock prospecting in the 1800s. While area gold mines were abandoned by 1900, seams of molybdenum above the Red River were mined in the tunnels and mills that were left behind.

Official Chevron Questa Mines history reports that residents were using this trace mineral for a primitive form of shoe polish. The first claims for mining molybdenum were staked in the Questa area in 1914 and equaled an area of 200 acres. It is unclear if a commercial market existed then for molybdenum, though tunneling a twisting mile underground, hand-drilling, and hauling ore by mule seems like a lot of trouble for shoe polish, so recorded history seems to be incomplete.

Why was Molybdenum of value?

Evidence has shown molybdenum’s use as an alloy in the production of Japanese Samurai swords dating back to the 14th century. Swedish scientist Carl Wilhelm Scheele studied this chemical element in the late 1700s, though it wasn’t until the late 1800s that extraction of large quantities became practical, after which interest increased in Europe and experiments demonstrated that molybdenum could replace tungsten in many steel alloys. A French company, Schneider and Co., was the first to market molybdenum use in production of armor plates. Demand for alloy steels were high during World War I and supplies of tungsten were limited, therefore research and development of this substitute ore increased. Another benefit: molybdenum weighs half as much as tungsten, thus its end products were easier to fabricate and transport.

The growth of Questa’s mine

Questa’s mining claims were acquired by Molycorp in 1921. Additional property was bought, soon expanding the mine from 200 acres to 14,300 acres. Molybdenum, known chemically as Mos2–not as black as charcoal and a bit softer than pencil lead–was even at that time hand-drilled and hauled by mules. Even this labor-intensive method eventually produced 50 tons of ore per day, with 50 miles of tunnels excavated by the mid-1950s, at which time the seam began to run out.

At a moment when the mine could have been abandoned, engineers found large near-surface reserves of ore, and in the late 1950-60s, Molycorp invested $40-million to transition to a thoroughly-mechanized open-pit mine. New Mexico Governor Jack M. Campbell dedicated this new operation in 1966, noting an economic transition in the U.S. from “meeting human needs to meeting human wants.” The booming economy of the 1960s produced many jobs for the area, and, much alloy for a multitude of products. Molycorp built one of North America’s first flotation concentrating plants, powered by the waters of the Red River. These famous trout waters flowed just below the mine. The mine had its own diesel-powered electric-generating station on site.

Soon, the mine was producing 10 million pounds of pure molybdenum concentrate per day. Blasters loosened the mountainside with large, controlled explosions, then diesel-electric trucks the size of 1-storey buildings dug into the loosened ore, with buckets holding 10 cubic yards, moving the ore to the milling area. Mechanical crushers broke the rock in stages, from 8” chunks, to 2-3” pieces, down to ½ – ¾ inches before feeding into liquid-filled ball mills for further crushing, then on to the flotation stage where the slurry was mixed with oil-based re-agents (closely guarded formulas) that created air bubbles to carry the ore to the tanks’ surfaces where it overflowed into additional vats. This process was repeated until a more concentrated pulp finally entered the dryer. Pure molybdenum powder emerged with all waste removed.

In 1977, Molycorp was bought by the major earth-resources company; Union Oil Co. of California (later named Unocal). A new higher-grade ore body was discovered much deeper in the mountain, and a ten-year, $250-million project transitioned the mine to go underground again.

The new underground construction began with two 1,300-foot-deep shafts; one a ventilation shaft to deliver air and a slurry of concrete, and the second 24 feet in diameter, had an advanced hoist system that lowered miners to the mine floor in a 2-minute-long descent. A third access into the mine was a 1 ½-mile tunnel drilled to reach under the main ore body. This contained a conveyer belt that delivered the ore to the surface at a rate of 12,000 tons per hour. At its peak, the mine operated 24 hours/day, 7 days/ week, all year long. Questa’s mine accounted for 10% of worldwide production and 15% of U.S. consumption for a time.

More than 10 miles of tunnel on two levels fed a gravity-block caving method of loosened ore falling in stages to the haulage level where it was transported by railroad cars to the conveyor belt. Traffic was directed from a control room on the surface. Above ground, the milling and flotation steps continued as before. The dry concentrate was transported in 8,000-pound steel containers by truck to Alamosa, Colorado, where it was then transported by rail to Pennsylvania for further processing.

What are molybdenum’s uses today?

Most molybdenum is used as a hardening agent in the steel industry. It is also used in cast-iron engine blocks, in energy pipelines, offshore oil platforms, and medical equipment, as well as for pigments, lubricants, and petroleum catalysts. Highly heat resistant, molybdenum is vital in the space industry to assure safe re-entry of spacecraft to the Earth’s atmosphere.

Problems downstream

While successive owners of the molybdenum mine in Questa promised to re-vegetate the mountainside as work was performed, and to design buildings and structures that blended into our beautiful scenery, and promised to return waters to the Red River in the pristine state, this proved problematic.

Mining of 18,000 tons of ore per day produced only 30 tons of molybdenum concentrate. 17,970 tons of waste remained each day. This liquid waste with its oil-based chemical re-agents filled surface pools on site where steps were taken to remove sediments and the remaining liquid was drained into rubber-lined 10” pipes that ran along State Highway 38 for 9 miles to tailings ponds southwest of the village of Questa. There the liquid dried and stabilizers were sprayed to reduce dust from drifting into the village. Rain and snowfall filled the ponds routinely and the ponds dried again plus groundwater was vulnerable to contaminated seepage.

The tailings pipeline crossed the Red River in several places and crossed farm land and residential property in Questa, with over 100 ruptures on record. Toxic tailings deposits, the result of pipeline breaks, have reportedly led to contaminated wells and health issues in a population that, for generations, had depended on the mine for most of its employment.

Amigos Bravos, a water conservation organization dedicated to protecting the waters of New Mexico, led the effort to hold the mine owners accountable. They worked with federal and state regulatory agencies, individuals, and community organizations to promote cleanup measures and to restore a healthy ecology to the Red River watershed.

Now a Superfund site

The molybdenum mine in Questa was placed on the National Priorities List (Superfund) by the Environmental Protection Agency in May 2000. It was declared a Superfund Cleanup Site in 2009.

The mine site’s waste rock dumps had been left un-reclaimed when the open pit operations ceased. Large quantities of heavy metals, dissolved when the rock was exposed to rain and snow, had contaminated both surface and groundwater below the mine. The Red River was reported to be technically dead for a distance of 8 miles until its confluence with the Rio Grande just south of the tailings ponds. The New Mexico Environment Department and other federal and state organization had documented the degraded state of the river for many years. The mine had been cited for pollution that resulted from broken tailings pipes many times.

Chevron inherited the mine in 2005 after a merger with Unocal, which already owned Molycorp, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The mine continued to function until June 1, 2014, when its employees were called together upon arriving for work and told the mine was closed forever as of that day. This proved catastrophic economically for many families of Questa.

Remediation and solar power

Chevron has continued to provide remediation, beginning with building a first-of-its-kind water treatment plant onsite to prevent further runoff or seepage of contaminants. They drained, dredged, lined, and landscaped the popular Eagle Rock Lake east of the village on the banks of the Red River. Groundwater in Questa, and the waters of the Red River are now reportedly clean. In 2016, the Justice Department, EPA, and the State of New Mexico announced a cleanup settlement of $143 million.

While much remediation work is yet to be completed, many eyes are on the project. Chevron Questa Mines has given many thousands of dollars of redevelopment funds to Questa. These are controlled by an economic development board, not by the governing body of the village. Chevron has also led the efforts to look toward a brighter and cleaner future in northern New Mexico, building a 20-acre solar farm adjacent to their obsolete tailings ponds where contaminated soil and water has been removed. This is a 1-megawatt concentrating photovoltaic (CPV) solar facility with about 175 solar panels. It provides enough power for Questa to live off-the-grid during daylight hours.

From a history of agriculture, mainly alfalfa, to generations working in an extractive industry, Questa has in many ways come full circle. It has returned to a lighter footprint on the land and to honoring a culture of resiliency in the face of hardship. This rugged, remote, and beautiful village is re-embracing the strength of its multicultural heritage and becoming a destination for lovers of the outdoors, from anglers to hikers, from artists to equestrians.

The mine is part of the cultural heritage of this area. Its new collaborative initiatives may shape Questa’s story for an ecologically brighter and economically more stable future for coming generations.

Resources:

Chevron Questa Mine, https://www.chevron.com/stories/life-after-mining

https://www.chevron.com/stories/solar

Amigos Bravos, https://amigosbravos.org/chevron-questa-mine they approved this text & use of link

Environmental Protection Agency, https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Cleanup&id=0600806#bkground

International Molybdenum Association, http://www.imoa.info/molybdenum/molybdenum-history.php

DVD compilation of the mine’s history, supplied by Chevron Questa Mines; ‘Questa Mine, a History in Film’