What is an oratorio?

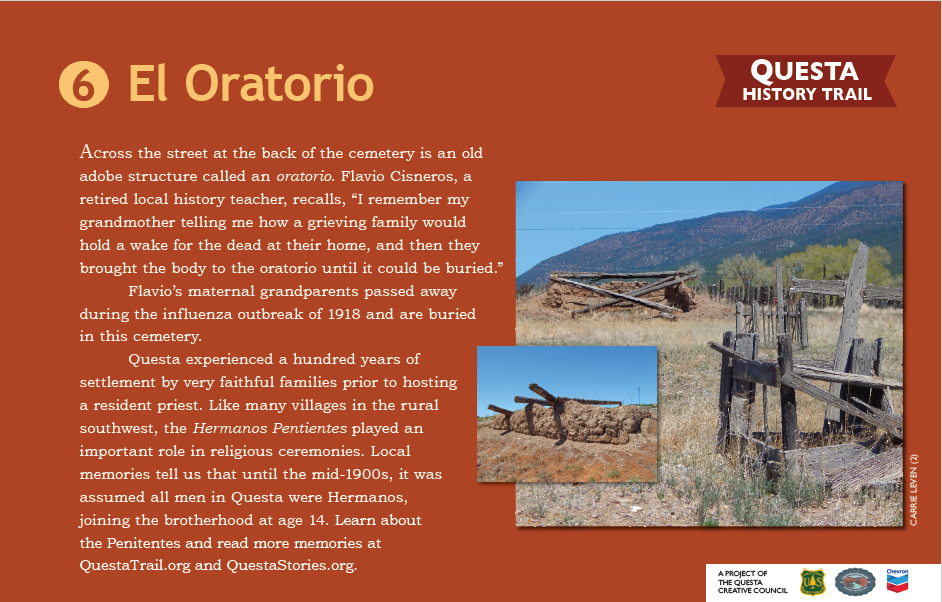

Only one oratorio existed in Questa, in the cemetery across the road from the historic church. The oratorio would have been used as long as the cemetery was active. It is difficult to read the earliest dates on the headstones, but this site was probably in use from the 1800s. Being outside the old plaza walls (no longer visible), this was located almost as close as it could have been, and may date to the earliest stable times of settlement in Questa – and stability did not come until the U.S. Cavalry arrived in the mid-1800s.

The cemetery holds remains of some who fell during the great influenza outbreak of 1918, and this seems to be when the cemetery filled and the new one across what is now State Highway 522 was begun.

According to oral histories (Flavio Cisneros) a family would hold the wake for the dead at their home, outside if weather and season permitted, then bring the body to the oratorio. The body was laid out on an adobe table and was only held here awaiting internment (while the grave was being prepared and the funeral organized) – probably not even overnight.

The oratorio was used by all residents, though all residents in Questa may not have been of the Catholic faith. An itinerant priest from Taos made the rounds of small parishes when the weather allowed, but without a resident priest always available, the Hermanos Penitentes played an important role. Local memories tell us that until the mid-1900s, it was assumed that all men in Questa were Hermanos. They joined the brotherhood at the age of 14.

Questa experienced a hundred years of settlement by very faithful families prior to the presence of a resident priest. Like many villages in the rural southwest, this was a classic situation where the practices of the Penitentes would have thrived.

While all residents could have utilized the oratorio, only the Hermanos worshiped in the local moradas, small and often hard-to-find or hard-to-identify adobe structures. There were three moradas within the village of Questa as it is today: one in the south end of the village off Lower Embargo Road, one to the east near the historic (abandoned) La Cienega school, and the third in Llano. The only surviving morada close by now is in Cerro.

A local Questeno recalls his mother telling that when she was a young girl, she accompanied a neighbor woman to the llano morada to do periodic upkeep; smoothing the mud floors, for example. She remembered floors that were caked with blood, indicating that self-flagellation did occur here. Many people see this as extreme, while practitioners who modeled themselves on the pure practices of Jesus, see this as a necessary step toward gaining forgiveness for their very human sins.

Read more about the history of the Penitentes, and their practices BELOW on this page.

Read an informative article from Manitos about Questa Creative Council’s Northern New Mexico Music; Past and Present project and its focus on the music of the Penitentes HERE, and watch a Facebook Live concert HERE. On May 21, 2021, musician Chris Arellano led this remote event filmed in the historic Costilla Plaza, sharing stories, history and playing the music of the Hermanos.

In contrast to historic conflict between Penitentes and the Catholic Church, the two practices co-exist today, and plans are being made to restore this oratorio and cemetery property in Questa.

A Brief History of the Penitentes

The Penitente Brotherhood, Los Hermanos Penitentes, has had great influence on the culture of rural northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Their presence continues to provide a service within communities, taking care of those in need, and offering comfort to those in mourning.

The practices of Los Hermanos may precede the life of St. Francis of Assisi whose philosophy, many believe, forms the basis of a Penitente lifestyle of deep devotion and simplicity; of living as Jesus lived.

Practices of self-inflicted pain that include lashing oneself until bleeding, carving into the skin during initiation ceremonies, and of walking a pilgrimage route carrying heavy wooden crosses, akin to that of Jesus Christ, is most notable to outsiders. These practices have been documented in Europe as early as 1200 AD, and seemed to arise in a void of priestly supervision, when rural lay-people, pre-literate, took their cue from religious imagery as opposed to following church doctrine.

These practices have existed in New Mexico since the southwest was settled and became very important after the Mexican Revolution, when Spain ceded the territory in 1821, and the Catholic Church removed its priests from the entire region. The Hermanos filled the void. Many credit them with taking care of the community, so the priests had a congregation to come back to.

Historic Origins

Los Hermanos de la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesus Nareno, the Brothers of the Pious Fraternity of Our Father Jesus of Nazareth, or sometimes, La Cofradia de Nuestra Padre Jesus Nazareno, the Fraternity of Our Father Jesus of Nazareth, dates back over 800 years, with its roots in Spain and Italy. Waves of popularity for this form of folk Catholicism are documented as far as the Alps, with reports of ten thousand Flagellantes marching across the countryside for Holy Week. Attempts by the Church to put down these practices during the Middle Ages often increased their popularity. A disastrous plague that raged in Germany in 1349 increased their numbers, and conflicts with the Church worsened. During the Inquisition, 91 members of the then-named Brothers of the Cross were burned at one incident in Sangerhusen, Germany.

Is there a direct lineage from these Flagellant practices among the men of Europe and the present Penitentes of New Mexico? Many believe that the practices were quite naturally brought across the ocean, died out in more populous areas of the New World, but survived in remote areas in the southwest where residents were isolated from new ideas, just as their language was isolated from changes over the centuries. Beliefs of ancestors persisted, and even became exaggerated in the absence of any moderating influence, and in the presence of a rugged life full of conflict and disease; a strong faith was needed.

Another interpretation of this history is that New Mexico’s Penitente practice represents the survival of the Third Order of St. Francis. A “third order” referring to lay practice, vs. the first and second order of living within the priesthood, or a monastery. The Franciscans, in the 13th century, introduced simple, straightforward customs that could easily be (according to the Church) exaggerated and corrupted by the laity.

This Third Order of St. Francis was commonly practiced in New Mexico during all of the Spanish era. Franciscan priests among the new settlers encouraged this. Wills documented over a 200-year period quite often show reference to the deceased having been a member of the Third Order and requesting a simple funeral in line with these practices. “I direct that when God, our Lord, shall see fit to call me out of this present life, my body be enshrouded in the habit of our father, San Francisco, of whose Third Order I am a brother, and that my funeral be modest.”

Following Mexico’s independence in 1821, the church pulled its priests out of New Mexico, and the Penitentes filled the void. When the United States took possession of the current southwest states, including our Rio Grande Valley in 1848, many residents still had strong allegiances to Spain. With the help of the Catholic Church, a program to “Americanize” the religious practices was begun. With its practices formally banned; the faithful Penitentes became a much more secret society.

The New Mexican practitioners were called, “Los hermanos penitentes de la tercer orden de San Francisco,” and there are records of the Archbishop of Santa Fe issuing stern communiques in the mid-1800s to the hermanos mayores to cease flagellation and the carrying of heavy crosses. Copies of the rules of the Third Order of St. Francis were enclosed so these could be followed in their original form without any “extreme” alterations. When this did not have the desired effect, the Penitentes were ordered to disband in 1889.

Moradas, small buildings for worship, often located in hard-to-spot locations, and buildings of adobe with no windows, became the new normal for these traditional worshipers. Some believe the moradas of the Rio Grande Valley were inspired by the area’s Native American kivas, sacred underground spaces where Tewa men still conduct private religious rituals.

During recovery from the Great Depression, a New Deal program called the Federal Writers’ Project, begun in 1935, sponsored many writers to venture into America’s rural communities and document the local culture and folklore. Some of these male writers reportedly infiltrated Penitente meetings and later wrote sensational reports of their practices. This created an even more secretive backlash that continued for decades.

The Catholic Church and the Penitentes have, to a great extent, reconciled, with Hermanos often leading the procession in church ceremonies to mark the Holy Week.

Information about the Practices of the Penitentes is easily found online. A synopsis can be found here.

Resources:

http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibits/swetc/spmc/body.1_div.34.html

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11635c.htm

http://www.elsantuariodechimayo.us/Santuario/Penitentes.html

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/04/03/penitentes-new-mexico_n_6990204.html